|

| (courtesy of Bing Image Creator) |

As I typed out that headline, it occurred to me that some readers might expect something about Roger Moore - so for their benefit, I'll insert a suitable photo from my collection to the bottom of this post. But what I really want to talk about is the legend-laden Dorset village of Whitchurch Canonicorum, which I wrote about in A Saint, a Spy and the Holy Grail back in 2014. The Holy Grail doesn't feature in this revisit, but both the Saint and the Spy do - thanks to some intriguing new information supplied by a reader of that earlier post.

When I came back to this blog after its long hiatus, I found the following comment awaiting moderation (fortunately only since January 2023 - a few other comments had been sitting in limbo for much longer than that!):

Bonjour, my name is Bruno Mevel. I used to live in Bridport and was involved in a play in Whitchurch years ago. The play was about the different possibilities as to who was Saint Wite. That play was written by a certain Christopher Dilke, journalist and author. He was also Georgi Markov's father-in-law... the reason why he is buried in Whitchurch. Don't know if this will reach you, if it does and you want some more info here is my mail address...I didn't actually publish that comment, as I didn't want to give Bruno's email to all the world's spambots, but I did contact him and he very kindly sent me quite a lot of info. But before I get into it, here's a quick reminder of our two protagonists:

- Saint Wite, also known as Saint Candida (from a Latin word meaning "white"), who probably lived in the early middle ages but about whom nothing is really known (though there are several legends and speculative theories). Her remains are interred inside the church of St Candida at Whitchurch Canonicorum - one of only two genuine church shrines to survive the Protestant reformation in England.

- Georgi Markov, a Bulgarian dissident who worked for the BBC. He wasn't actually a spy, but he was accused of spreading anti-communist propaganda by his former compatriots. One morning in 1978, while he was waiting at a London bus stop on his way to work, some still-unknown assailant shot him in the leg with a sugar-coated ricin pellet fired from a rolled up umbrella (you can't do this with any old umbrella, by the way - you need a specially modified one from the Bulgarian equivalent of Q branch). Markov died a few days later, and he's buried in the churchyard of Whitchurch Canonicorum, with a gravestone inscribed in both English and Cyrillic.

In my earlier post, I said I couldn't find out how Markov came to be buried in a Dorset village churchyard - so that's one thing Bruno has cleared up, with the revelation that Markov was married to someone from that area. As well as expanding on this point, the additional information he sent also revealed a rather roundabout connection between Markov and St Wite herself. Here's a summary of the whole story.

In his comment above, Bruno mentioned that Georgi Markov's father-in-law was an author named Christopher Dilke (1913–87). In his later years Dilke moved to Whitchurch Canonicorum, where he wrote a play called Legends of St Wite for the church's 900th anniversary in July 1980 (I found this mention of it on the church's own website). Bruno happened to share mutual friends with the Dilke family, and Christopher Dilke asked him to perform one of the roles in the play. The plot involved a new Saxon bishop placed in charge of Whitchurch trying to ascertain just who St Wite was. In the process, he asks various people to give their opinions on the matter. Bruno (who is French) played the role of a Breton nobleman, presenting the Breton version of the St Wite legend.

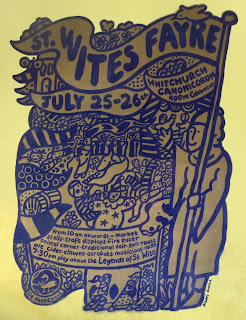

The play was only performed once, inside the church itself. As much as anything, Bruno remembers the costumes they made for themselves, which were copied from the Bayeux tapestry (if you subtract 900 from 1980 and remember your history, you'll see this gets the period pretty much spot-on). Bruno also kept hold of the poster from the event, which was designed by a local artist named Albert Duplock. Here it is:

Switching over to the Markov story, there's a connection with Christopher Dilke there too, because Markov married Dilke's daughter Annabel in 1975. After Markov's murder three years later, Annabel's mother claimed the Soviet KGB must have supplied the ricin that was used. This was the height of the Cold War, remember, when East-West espionage and intrigue was at its most intense. During Markov's funeral in St Candida's churchyard, the mourners - who included several other Bulgarian defectors - were protected by armed Special Branch officers who mingled discreetly with them.

As for the Roger Moore connection I mentioned - well, there isn't one really, except with my "The Saint and the Spy" title. Moore is best known, of course, for playing the most famous fictional spy of all, James Bond, in the 1970s and 80s, but those of us of a certain age also fondly remember him in the TV adaptation of The Saint, by Leslie Charteris, in the 1960s. In that series, Moore's character drove a distinctive white Volvo P1800 coupe, which I happened to see at the Bristol Classic Car Show in 2017. Here's my photo of it:

In case you can't decipher the label on the windscreen, here's what it amounts to: This is the original Roger Moore "ST 1" 1962 TV Saint car. It was used in the first series and made its debut in the first episode [...] The registration "ST 1" was only used for filming - actual reg is 71 DXC.