The other paperback shown above is a non-fiction one, The Psychic Detectives (1984), which I bought in 2016 when I was researching my own book, Pseudoscience and Science Fiction. Here's what I said about Wilson there:

As his career progressed, he became increasingly fascinated with the world of strange powers. A recurrent theme throughout his fiction and non-fiction is that most people live a robotic existence far below their real potential.That use of the word "robotic" brings me on to the main subject of this post, which is the Kindle book shown in the above photo - Gary Lachman's Beyond the Robot: The Life and Work of Colin Wilson (2016). I only became aware of it last month, when Gary posted the following on Facebook:

I've just heard that the paperback of Beyond the Robot, my book about Colin Wilson, is now out of print. If you are among the many who didn't buy a copy, there's still time to not get the Kindle edition too.Since I'm a chronic sufferer from the "Why do friends never read my books?" syndrome, I clearly had to buy it immediately! I'm glad I did, as I found it a fascinating and information-packed read which got 5 out of 5 stars from me on Goodreads. However, this post isn't really a review of the book, so much as a summary of a few things I found particularly interesting from a fortean point of view.

To start with, Fortean Times (as well as some of the "Unconventions" they organized) makes several appearances in the book. At one point Lachman specifically mentions "writing pretty regularly for the Fortean Times", and after Colin Wilson's death in 2013 Gary's obituary of him appeared in FT 310 (the same issue as my review of a comic-strip book about particle physics, FWIW). Although I've never actually met Gary, I did spot him at a couple of Uncons - and, I think, in the audience at the "Aliens and the Imagination" event I mentioned on this blog in 2011. Way back in 1978, in the guise of his musical alter-ego Gary Valentine, Lachman also wrote Blondie's paranormal-themed hit "I’m Always Touched by Your Presence, Dear".

As for Colin Wilson himself, he only came on to fortean-type subjects a decade or so after he started writing. His original focus was on existential philosophy, and his first book on that subject, The Outsider, was published in 1956 when he was just 24. It received a lot of rave reviews, including one in The Observer - which Lachman describes as one of Britain's "highbrow Sunday papers" (which pleased me a lot, since they published a two-page feature by me just a couple of months ago).

In hindsight, it's not surprising that Wilson's own personal take on philosophy eventually led to an interest in the paranormal, since it's ultimately all about widening human consciousness beyond the normal trivialities of everyday life. That's why he was drawn to the Lovecraftian style of fiction - he had no time for the more mainstream kind of novelist "who, in the service of realism, simply portrays life as it is". Another fortean favourite who made an impression on Wilson was Aleister Crowley. According to Lachman, Crowley was the model for one of the characters in Wilson's early novel Man Without a Shadow (1963) - Carradoc Cunningham, an occultist and master of "sex magic". Apparently Wilson himself harboured interests along the latter lines, believing that sexual orgasm can unlock higher states of consciousness and "open the doors of perception".

When Wilson came to write about the paranormal - The Occult (1971) being his first and best-known, but far from only, book on the subject - he did so in a way that was almost diametrically opposed to the standard approach for the genre. As Lachman puts it:

If scientists and other skeptics were ever going to broaden their minds about the occult, then it had to be presented to them logically, in a way that made sense, not in a sensational "believe it or not" manner.As with his first book about philosophy, Wilson's first book on the paranormal also got rave reviews. In part, this was because "highbrow" readers were far more open to such topics at that time than they are today. Referring to a favourable review that New Scientist gave of Wilson's follow-up book Mysteries (1978), Lachman says:

Such acclaim from a scientific publication for a book about the paranormal is unusual today, and shows that in the 1970s, the paranormal was treated with respect by many scientists, unlike in our more narrowly skeptical times.Another thing I remember myself from those times, is that interest in fringe topics was much more wide-ranging and eclectic than it is today. The "paranormal", for example, meant a lot more than just ghosts and poltergeists. Listing some of the topics that Wilson covered in Mysteries, Lachman includes "plant telepathy, psychic surgery, transcendental meditation, biofeedback, Kirlian photography, multiple personality and synchronicity". All great stuff - makes me feel more nostalgic than ever for the 20th century!

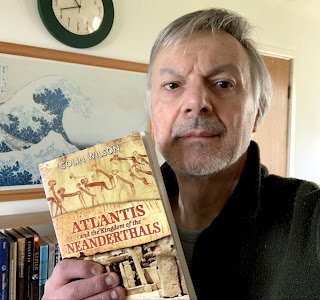

Colin Wilson was an incredibly prolific author, and I kept noting down titles of books of his that I ought to seek out. The most intriguing-sounding of all is Atlantis and the Kingdom of the Neanderthals (2006) - something I should have known about already, as Wilson mentioned it in an article he himself wrote for Fortean Times, called "A 100,000-year-old Civilization?" It appeared in FT 272 in March 2011, and I have to admit I'd forgotten all about it (although I looked back at it just now, which is how I know it mentions the Atlantis book). In any case, I've already acquired my copy of Atlantis and the Kingdom of the Neanderthals from eBay, as you can see here: