In the comment thread to last week's post, I mentioned that Fortean Times occasionally touches on various aspects of popular culture, from cult TV and movies to comics and pop music. So I thought I'd do a quick run-through of a few examples today.

To start with some very obvious topics, there are the three shown above. The X-Files (FT 82, August 1995) was not only one of the most fortean TV shows of all time, but its first appearance in 1993 coincided with the wider distribution of FT to "mainstream" retailers like WH Smith, and almost certainly contributed to the magazine's popularity at that time. Around a decade later, Dan Brown's novel The Da Vinci Code (FT 193, March 2005) was a publishing phenomenon, bringing fringe theories that had previously been the realm of specialist writers (and FT contributors) like Lionel Fanthorpe and Lynn Picknett to a much wider audience. Just over a century earlier, Bram Stoker had done something similar in his novel Dracula - the title character of which went on to become one of the most recognisable and ubiquitous pop-culture icons of them all, as recounted in the cover feature of FT 257 (January 2010).

At a less obvious level, you can find references to popular culture in almost every issue of FT. Taking the one I discussed last week, for example - FT 73 from February/March 1994 - there's an interview with cult author William Gibson, generally credited as the originator of the cyberpunk genre. And I spotted something else in that issue, too: a book review by comics legend Alan Moore. I don't mean a review of one of his graphic novels - I mean a review written by him of someone else's work. Looking online, I see he actually did quite a few reviews for FT in those days - which pleases me enormously, as I've done over 40 of them myself. It's always nice to discover that you have something in common with a famous person!

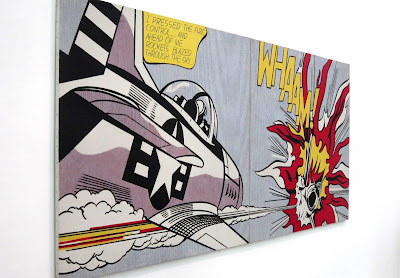

Sticking with books and comics for a moment, here are three more covers that caught my eye. No apologies for a second appearance of The Da Vinci Code (FT 212 this time, from August 2006) - both because it's one of my favourite novels, and because I love the illustration on the cover. In addition to people like Picasso and Orson Welles, it features Da Vinci himself in the act of strangling Dan Brown! The middle cover (FT 256, December 2009) features Dennis Wheatley - best remembered today for The Devil Rides Out (the only one of his novels that I've read), although in his day he was Britain's most prolific author of occult fiction. Finally there's the only comics-themed cover I could find - FT 320 (November 2014), relating to the Fredric Wertham-inspired anti-comics paranoia than swept America in the 1950s.

I found a few shorter comic-related pieces on interior pages as well. The most interesting of these was an article in FT 277 (July 2011) called "The Morning of the Mutants", speculating that Stan Lee and/or Jack Kirby got the idea for the X-Men from the seminal (though now largely forgotten) fortean conspiracy book The Morning of the Magicians, written in 1960 by Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier. There's also a feature about Marvel Comics' Doctor Strange in FT 349 (January 2017, to tie in with the movie), which discusses the character's origin and fictional predecessors.

Regarding the "popular culture" of the mid-20th century, I can't resist mentioning a couple of pieces by myself - in fact the only two full-length feature articles I've had in FT. First there was "Fanthorpe's Fortean Fiction" (FT 297, February 2013) about the large number of mass-market paperback novels that Lionel Fanthorpe churned out in the late 1950s and early 60s. This was followed by "Astounding Science, Amazing Theories" (FT 355, July 2017), looking at fortean themes in the pulp science fiction magazines of the 1940s.

Pulp magazines were a huge part of popular culture in the first half of the 20th century, but - with a few notable exceptions - they're only of interest to die-hard fans today. Of those exceptions, perhaps the most important is H. P. Lovecraft, whose Cthulhu Mythos first took form in the pages of Weird Tales in the 1920s and 30s, before going on to develop a life of its own to rival that of Bram Stoker's Dracula. I found no fewer than three Lovecraft-inspired FT covers: FT 184 (June 2004), FT 369 (August 2018) and FT 390 (March 2020 - this one tying in with the movie adaptation of The Color Out of Space). Here they are:

As regards cult TV shows, I've already mentioned the most fortean of all, The X-Files - which not surprisingly made several further appearances after the one pictured at the top of this post (including FT 85 from February 1996, which had a rundown of all the fortean references in the show's first season). Three other TV-related covers are shown below, the middle of which - FT 215 from October 2006, celebrating 40 years of Star Trek - needs no introduction. The other two relate to the screenwriters (both with wider fortean interests than you might expect) behind two of Britain's most famous sci-fi icons: Kit Pedler, who created Doctor Who's second-most-famous villains, the Cybermen (FT 209, May 2006), and Nigel Kneale, creator of Professor Quatermass (FT 418, May 2022). The latter may no longer be a household name, but back in the 1950s he was really the first great TV sci-fi hero, in this country at least.

Turning to movies - I was spoiled for choice here, so I've picked out three covers that really speak for themselves. First there's a celebration of 50 years of Hammer Horror films (FT 223, June 2007), then a look at one of the mainstays of those films, Peter Cushing, on the 100th anniversary of his birth (FT 301, May 2013), and finally a 40-years-on retrospective about The Exorcist (FT 313, April 2014):

To be honest, my favourite thing about The Exorcist is the music - the snippet from Mike Oldfield's Tubular Bells that it uses, I mean - which brings me neatly onto the next subject. When I talk about "pop culture" on this blog, I most often mean fairly specialized things like pulp magazines, comics (from the pre-multimedia franchise days) and cult TV shows such as The X-Files. But to most people, pop culture means just one thing, and that's pop music. This is such a pervasive part of modern life that it's acquired a plethora of fortean connections - so much so that I'm going to split them into two distinct parts.

To start with, here are three cover features that deal with direct fortean influences on musicians. The first, from FT 88 back in July 1996, describes how various pop stars from David Bowie and Jimi Hendrix to Kate Bush and The Orb absorbed ufological and similar speculations into their music. Second, there's a somewhat more arcane take on the same subject by Ian Simmons (FT 244, January 2009), featuring the likes of Stockhausen and Sun Ra - a much-referenced source for my own book The Science of Sci-Fi Music. Finally, in the immediate wake of David Bowie's death, there was a cover feature about the numerous fortean influences on his work (FT 338, March 2016) - including the aforementioned Morning of the Magicians by Pauwels and Bergier.

Another aspect of pop music that's of fortean interest is the way weird conspiracy theories grow up around the subject. So to round off what I honestly believed would be a shorter-than-usual post when I started it, but has ended up as probably my longest ever - here are three cover features addressing this aspect. The one on the left (FT 166, January 2003) deals with the numerous legends and conspiracy theories associated with Elvis, while the one on the right (FT 384, October 2019) does much the same for the Beatles. As for the one in the middle (FT 258, February 2010), it concerns the notion that the "Illuminati" employ popular music - and the musicians themselves - to manipulate the thoughts, beliefs and behaviour of the general public. But that's not really a conspiracy theory, is it? I mean, if you substitute "global media" for "Illuminati", I'd say it's an indisputable fact.