The evocatively named Hell-Fire Caves in West Wycombe were originally excavated for a very practical reason – to quarry chalk for a new road to neighbouring High Wycombe. But the person behind the project, Sir Francis Dashwood, had the tunnels carved in a strange symbolic design (see top left picture), somewhat reminiscent of a modern-day crop formation. The caves were finished in 1752, and for the next ten years they served as the meeting place of Dashwood’s mysterious “Hell-Fire Club”.

I wrote about the Hell-Fire Caves on a previous occasion, using a picture that Paul Jackson sent me (and Paul has written about the site on his own blog). But I finally got around to visiting the caves myself last week, so I can show some of my own photos!

Actually “the Hell-Fire Club” seems to have been a pejorative term applied by outsiders – Dashwood and company actually referred to themselves as “The Knights of St Francis of Wycombe” (or sometimes “Friars” rather than “Knights”). Many of them were prominent poets, politicians and doctors – Dashwood himself was Chancellor of the Exchequer at one point. Other famous members included the Earl of Sandwich (who served as First Lord of the Admiralty, as well as inventing the sandwich) and the great painter and cartoonist William Hogarth (who is fortean enough to have appeared on this blog at least four times – here and here and here and here). Benjamin Franklin, one of America’s Founding Fathers, wasn’t a member of the club but is known to have visited the caves on more than one occasion (as depicted in the bottom right photo).

The caves contain a strange mixture of Christianity (as in the references to St Francis and Friars) and pre-Christian mythology (such as the statue of Venus that can be seen in the bottom left photo). The final chamber has the pagan-sounding name of “The Inner Temple”, and is located some hundred metres directly below the Christian church on top of the hill. Undoubtedly this helped give rise to the various rumours of “satanic” goings-on at the Hell-Fire Club. Personally, I’m increasingly sceptical about this – remember it was a time when the God-fearing masses believed anyone who read a book other than the Bible was a closet Satanist. Instead, I think Dashwood and his circle were just indulging in fashionable romantic fantasies about Graeco-Roman culture (a bit like the Stourhead temples I wrote about last year, which also date from the 1750s).

Normally when I hear about a “family mausoleum” in a churchyard I think of something comparable in size to my garden shed. Dashwood’s mausoleum, which he built on the hill directly above the Hell-Fire caves around the same time, is more like a small fortress:

Andrew May's Forteana Blog, focusing on the weirder fringes of history (and other old-fashioned stuff)

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Symbolism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Symbolism. Show all posts

Sunday, 19 June 2016

Sunday, 28 December 2014

Retro-Fortean Answers

Here are the answers to last week’s Retro-Fortean Crossword. Wherever possible the clues were based on previous blog posts – in which case I’ve included a link to the relevant post.

ACROSS

1. AMBROSE Bierce, who vanished without a trace in December 1913 (See The Ambrose Collector)

5. Generic term for a mystery animal: CRYPTID (As in the Cryptid Casebook series – see The Science of Bigfoot for my contribution to the series)

9. Nickname of Raymond A. Palmer, pulp magazine editor who popularized the Shaver Mystery: RAP (My copy of the special “Shaver Mystery” issue of Amazing Stories, dated June 1947, can be seen in the photograph above)

10. “The EERIEST Ruined Dawn World”, short story by Fritz Leiber

11. Secretive organization that Edward Snowden used to work for: NSA (As featured in Satire and the Internet)

12. Fictional country which is the source of Doc Savage’s wealth: HIDALGO (The Doc Savage trade paperback pictured above includes a comic-book adaptation of Doc’s origin story, set in Hidalgo)

13. “POST HOC ergo propter hoc”, a logical fallacy popular with some conspiracy theorists

14. A short 16 mm film clip from 1967 purportedly showing Bigfoot: PATTERSON-GIMLIN (See Patterson-Gimlin Film Fake or Fact)

19. Village in the South of France reputedly associated with a great mystical secret: RENNES-LE-CHATEAU (See The Devil of Rennes-le-Chateau)

21. Ankh, cross and pentagram, for example: SYMBOLS

24. A Runic alphabet: FUTHARK

27. LEN Wein, creator of Wolverine and Swamp Thing (My copy of Wolverine’s first appearance was featured in The Marvel Age of Comics)

28. Hard to pin down, like many Fortean phenomena: ELUSIVE

29. Like a UFO, but not unidentified: IFO

30. An unexplained event: ANOMALY

31. SHANNON McMahon, X-Files super-soldier played by Lucy Lawless

DOWN

1. Early type of UFO widely reported across America during the 1890s: AIRSHIP

2. Bigfoot, for example: BIPED

3. Denny O’NEIL, author of The Shadow 1941: Hitler’s Astrologer (See Hitler’s Astrologer)

4. If the Gunpowder Plot was a False Flag operation, this person may have engineered it: EARL OF SALISBURY (As described in my Conspiracy History book)

5. A famous Fortean mystery from Barbados: CREEPING COFFINS (See Creeping Coffins)

6. Himalayan giant apes (real or imaginary): YETIS

7. Enigmatic alien creature in Philip K. Dick’s novel A Maze of Death: TENCH (My copy, which I originally read in 1980, is pictured above)

8. A type of scientific analysis applied to Bigfoot and Richard III: DNA SCAN (See Bigfoot, Richard III and Outsider Science)

15. The TEN Lost Tribes of Israel

16. The Third EYE, by T. Lobsang Rampa

17. IRA Levin, author of Rosemary’s Baby and The Stepford Wives

18. First name of JFK’s alleged assassin: LEE

19. A water nymph in Slavic mythology RUSALKA (As mentioned in my novelette The Mechanical Gorilla)

20. Pulp magazine which featured Eric Frank Russell’s Sinister Barrier in its first issue: UNKNOWN (See Sinister Barrier: the first Fortean novel and Pulp Forteana)

22. Planet ruled by Ming the Merciless in Flash Gordon’s universe: MONGO

23. The Magic Flute or The Flying Dutchman, for example: OPERA (See Fortean Opera)

25. Huge volcanic eruption which may have been responsible for the Atlantis legend: THERA

26. Entity from another planet: ALIEN

ACROSS

1. AMBROSE Bierce, who vanished without a trace in December 1913 (See The Ambrose Collector)

5. Generic term for a mystery animal: CRYPTID (As in the Cryptid Casebook series – see The Science of Bigfoot for my contribution to the series)

9. Nickname of Raymond A. Palmer, pulp magazine editor who popularized the Shaver Mystery: RAP (My copy of the special “Shaver Mystery” issue of Amazing Stories, dated June 1947, can be seen in the photograph above)

10. “The EERIEST Ruined Dawn World”, short story by Fritz Leiber

11. Secretive organization that Edward Snowden used to work for: NSA (As featured in Satire and the Internet)

12. Fictional country which is the source of Doc Savage’s wealth: HIDALGO (The Doc Savage trade paperback pictured above includes a comic-book adaptation of Doc’s origin story, set in Hidalgo)

13. “POST HOC ergo propter hoc”, a logical fallacy popular with some conspiracy theorists

14. A short 16 mm film clip from 1967 purportedly showing Bigfoot: PATTERSON-GIMLIN (See Patterson-Gimlin Film Fake or Fact)

19. Village in the South of France reputedly associated with a great mystical secret: RENNES-LE-CHATEAU (See The Devil of Rennes-le-Chateau)

21. Ankh, cross and pentagram, for example: SYMBOLS

24. A Runic alphabet: FUTHARK

27. LEN Wein, creator of Wolverine and Swamp Thing (My copy of Wolverine’s first appearance was featured in The Marvel Age of Comics)

28. Hard to pin down, like many Fortean phenomena: ELUSIVE

29. Like a UFO, but not unidentified: IFO

30. An unexplained event: ANOMALY

31. SHANNON McMahon, X-Files super-soldier played by Lucy Lawless

DOWN

1. Early type of UFO widely reported across America during the 1890s: AIRSHIP

2. Bigfoot, for example: BIPED

3. Denny O’NEIL, author of The Shadow 1941: Hitler’s Astrologer (See Hitler’s Astrologer)

4. If the Gunpowder Plot was a False Flag operation, this person may have engineered it: EARL OF SALISBURY (As described in my Conspiracy History book)

5. A famous Fortean mystery from Barbados: CREEPING COFFINS (See Creeping Coffins)

6. Himalayan giant apes (real or imaginary): YETIS

7. Enigmatic alien creature in Philip K. Dick’s novel A Maze of Death: TENCH (My copy, which I originally read in 1980, is pictured above)

8. A type of scientific analysis applied to Bigfoot and Richard III: DNA SCAN (See Bigfoot, Richard III and Outsider Science)

15. The TEN Lost Tribes of Israel

16. The Third EYE, by T. Lobsang Rampa

17. IRA Levin, author of Rosemary’s Baby and The Stepford Wives

18. First name of JFK’s alleged assassin: LEE

19. A water nymph in Slavic mythology RUSALKA (As mentioned in my novelette The Mechanical Gorilla)

20. Pulp magazine which featured Eric Frank Russell’s Sinister Barrier in its first issue: UNKNOWN (See Sinister Barrier: the first Fortean novel and Pulp Forteana)

22. Planet ruled by Ming the Merciless in Flash Gordon’s universe: MONGO

23. The Magic Flute or The Flying Dutchman, for example: OPERA (See Fortean Opera)

25. Huge volcanic eruption which may have been responsible for the Atlantis legend: THERA

26. Entity from another planet: ALIEN

Labels:

Atlantis,

comics,

Conspiracy theories,

crosswords,

Cryptozoology,

Eric Frank Russell,

nostalgia,

Philip K. Dick,

Pulp magazines,

Rennes-le-Chateau,

Richard Shaver,

science fiction,

Symbolism,

ufology

Sunday, 23 February 2014

Satan, Sin and Death

The dramatic scene depicted above is the work of the 18th century painter and engraver William Hogarth. This particular engraving is based on a painting he produced circa 1735-40, but it’s easier to see what’s going on in this black-and-white version. It’s a scene from Milton’s Paradise Lost in which Satan, en route from Hell to Earth, encounters two strange figures guarding the Gates of Hell:

Before the gates there sat on either side a formidable Shape. The one seemed woman to the waist, and fair, but ended foul in many a scaly fold, voluminous and vast – a serpent armed with mortal sting. [...] The other Shape – if shape it might be called, that shape had none distinguishable in member, joint, or limb. Or substance might be called that shadow seemed, for each seemed either. Black it stood as Night, fierce as ten Furies, terrible as Hell, and shook a dreadful dart.

The first figure is the personification of Sin, while the second figure is Death. It’s interesting that Satan himself is portrayed in relatively heroic form, although his facial features look more monstrous in the original painted version than in this engraving.

“Satan, Sin and Death” is an unusual departure for Hogarth, most of whose works are satirical in nature (see for example Paranormal investigation, 18th century style and Another historical myth-conception). Hogarthian satire was pretty gentle stuff, aimed at broad social classes rather than at specific individuals. By the end of the 18th century, however, all that had changed – and political caricatures were every bit as viciously ad hominem as they are today.

James Gillray (1756 – 1815) was one of the first great political cartoonists. His own variation on the theme of “Sin, Death and the Devil”, dating from 1792, is shown below. Death is represented by the Prime Minister of the time, William Pitt the Younger, while the Devil is Pitt’s Lord Chancellor, Baron Thurlow. They are separated by the figure of Sin in the person of Queen Charlotte, the wife of King George III. Even today, the depiction of the present Queen in such an unflattering way would be frowned on in some quarters (although Conspiracy Theorists might detect a resemblance between Her Majesty and Milton’s personification of Sin, in that both of them are half reptilian).

William Blake (mentioned previously in A 19th Century Contactee and Reinventing Ezekiel's Wheel) was born the year after Gillray. He had something of an obsession with Milton’s Paradise Lost, producing at least 30 illustrations based on it. The earlier of Blake’s two versions of “Satan, Sin and Death” (circa 1807) is depicted below. Like Hogarth, Blake makes the figure of Satan look surprisingly heroic... while his version of Death is a semi-transparent ghost.

Before the gates there sat on either side a formidable Shape. The one seemed woman to the waist, and fair, but ended foul in many a scaly fold, voluminous and vast – a serpent armed with mortal sting. [...] The other Shape – if shape it might be called, that shape had none distinguishable in member, joint, or limb. Or substance might be called that shadow seemed, for each seemed either. Black it stood as Night, fierce as ten Furies, terrible as Hell, and shook a dreadful dart.

The first figure is the personification of Sin, while the second figure is Death. It’s interesting that Satan himself is portrayed in relatively heroic form, although his facial features look more monstrous in the original painted version than in this engraving.

“Satan, Sin and Death” is an unusual departure for Hogarth, most of whose works are satirical in nature (see for example Paranormal investigation, 18th century style and Another historical myth-conception). Hogarthian satire was pretty gentle stuff, aimed at broad social classes rather than at specific individuals. By the end of the 18th century, however, all that had changed – and political caricatures were every bit as viciously ad hominem as they are today.

James Gillray (1756 – 1815) was one of the first great political cartoonists. His own variation on the theme of “Sin, Death and the Devil”, dating from 1792, is shown below. Death is represented by the Prime Minister of the time, William Pitt the Younger, while the Devil is Pitt’s Lord Chancellor, Baron Thurlow. They are separated by the figure of Sin in the person of Queen Charlotte, the wife of King George III. Even today, the depiction of the present Queen in such an unflattering way would be frowned on in some quarters (although Conspiracy Theorists might detect a resemblance between Her Majesty and Milton’s personification of Sin, in that both of them are half reptilian).

William Blake (mentioned previously in A 19th Century Contactee and Reinventing Ezekiel's Wheel) was born the year after Gillray. He had something of an obsession with Milton’s Paradise Lost, producing at least 30 illustrations based on it. The earlier of Blake’s two versions of “Satan, Sin and Death” (circa 1807) is depicted below. Like Hogarth, Blake makes the figure of Satan look surprisingly heroic... while his version of Death is a semi-transparent ghost.

Sunday, 20 October 2013

Phallic Symbols (mostly small ones)

When I first spotted this statue of Balzac at the Musée Rodin in Paris, I though it was something else altogether. But I was wrong. Gigantic erections are something you almost never see in mainstream European art. I’m not sure why, because male genitalia are hardly a rarity in classical sculptures and paintings. It’s just that they always seem to be little ones.

There is a word for the artistic representation of an erect penis: ithyphallic. You can do a Google image search for “ithyphallic” if you want to, but you’ll be disappointed – most of the results come from the ancient world (where erections were believed to have magical properties – see Phascinating Phacts). It all changed with the Renaissance – big dicks were out and tiny dicks were in. The result is particularly comical in the case of mythological figures like the Greek god Zeus (≈ the Roman god Jupiter), who spent much of his career inseminating females. The only picture I’ve found that shows him with anything approaching a hard-on is a fresco by the 16th century Italian painter Giulio Romano, depicting Jupiter seducing Olympia.

Although some ancient Roman figures are shown with enormous erections, these always seem to depict specifically “phallic” gods such as Priapus. Even the great hero Hercules is generally shown with an unheroic little wiener, despite having an otherwise heavily muscled physique and heroic posture. Usually, anyhow. I saw this irreverent statue of Hercules at the British Museum’s Pompeii exhibition earlier this year (photography wasn’t allowed, so this is an official image, not mine). Notice how his dick is smaller than his little finger.

It’s not just the great mythological figures of Europe who are underendowed in the genital department. There’s a type of statue you sometimes see that I used to think of as a “naked Buddha”, but actually they don’t depict the Buddha at all – they come from another Asian religion called Jainism.

According to the label on the statue depicted here, which I saw in London’s V&A Museum, it depicts the Jina Parshvanatha, the 23rd Jain saviour, engaged in “sky-clad” meditation. His penis is about the same size as his thumb.

The Buddha is described in a Mahāyāna text called the Gaṇḍhavyūha as having a sex organ “like a thoroughbred elephant or stallion”, that can be retracted into his body when not in use. Presumably for that reason, depictions of the Buddha never show his penis – in fact the clingy drapery sometimes shows the very obvious absence of a penis.

Nevertheless, like Zeus or Jupiter, there’s no doubt the Buddha knew how to use it – witness the countless images of Buddha-incarnations copulating with female consorts (in the Tantric form of Buddhism at least). Here’s one I saw on my recent trip to Paris, in the Musée Guimet. It’s a type of devotional painting called a thangka, although at first glance you could be forgiven for thinking it was an example of early mediaeval interracial porn...

There is a word for the artistic representation of an erect penis: ithyphallic. You can do a Google image search for “ithyphallic” if you want to, but you’ll be disappointed – most of the results come from the ancient world (where erections were believed to have magical properties – see Phascinating Phacts). It all changed with the Renaissance – big dicks were out and tiny dicks were in. The result is particularly comical in the case of mythological figures like the Greek god Zeus (≈ the Roman god Jupiter), who spent much of his career inseminating females. The only picture I’ve found that shows him with anything approaching a hard-on is a fresco by the 16th century Italian painter Giulio Romano, depicting Jupiter seducing Olympia.

Although some ancient Roman figures are shown with enormous erections, these always seem to depict specifically “phallic” gods such as Priapus. Even the great hero Hercules is generally shown with an unheroic little wiener, despite having an otherwise heavily muscled physique and heroic posture. Usually, anyhow. I saw this irreverent statue of Hercules at the British Museum’s Pompeii exhibition earlier this year (photography wasn’t allowed, so this is an official image, not mine). Notice how his dick is smaller than his little finger.

It’s not just the great mythological figures of Europe who are underendowed in the genital department. There’s a type of statue you sometimes see that I used to think of as a “naked Buddha”, but actually they don’t depict the Buddha at all – they come from another Asian religion called Jainism.

According to the label on the statue depicted here, which I saw in London’s V&A Museum, it depicts the Jina Parshvanatha, the 23rd Jain saviour, engaged in “sky-clad” meditation. His penis is about the same size as his thumb.

The Buddha is described in a Mahāyāna text called the Gaṇḍhavyūha as having a sex organ “like a thoroughbred elephant or stallion”, that can be retracted into his body when not in use. Presumably for that reason, depictions of the Buddha never show his penis – in fact the clingy drapery sometimes shows the very obvious absence of a penis.

Nevertheless, like Zeus or Jupiter, there’s no doubt the Buddha knew how to use it – witness the countless images of Buddha-incarnations copulating with female consorts (in the Tantric form of Buddhism at least). Here’s one I saw on my recent trip to Paris, in the Musée Guimet. It’s a type of devotional painting called a thangka, although at first glance you could be forgiven for thinking it was an example of early mediaeval interracial porn...

Labels:

Art,

Buddhism,

museums,

mythology,

Phallicism,

Sacred sex,

Symbolism

Friday, 20 September 2013

The Scarab and the Stars

Earlier this year a scientific paper was published with the eyecatching title “Dung Beetles Use the Milky Way for Orientation”, which was widely reported in the mainstream media. The research has now been awarded one of the 2013 Ig Nobel Prizes – the “Joint Prize in Biology and Astronomy”.

Actually the result isn’t as outrageous as it sounds. The problem is that people focus on the symbolic associations of words, rather than the underlying thing a word is being used to describe. So a really basic image-processing task, because of the way it’s described, suddenly takes on cosmic or mystical significance. The mystical dimension is enhanced by the fact that the dung beetle, under its alternative name of Scarab, was a sacred symbol in ancient Egypt that has now become a favourite of New Agers.

Stars also have a New Age connection, via astrology. This is one of the reasons – alongside associations with UFOs and science fiction – that any mention of “the stars” is likely to provoke a giggle reflex in the general public. But this is because people are focusing on the layers of associations superimposed on words, rather than what words actually mean. Living in the modern world, we have a complex mental model of what a star is. But from a purely empirical perspective, the stars are just points of light in the sky.

Needless to say, a scarab beetle doesn’t carry along any intellectual baggage regarding the scientific and cultural associations of the stars. It just knows it can see them, because they’re there (in this respect, the beetle is closer to reality than most humans, who read all about outer space on the internet but rarely look up at the night sky). From the beetle’s point of view, there is survival value in being able to travel in a straight line. By trial and error over countless generations, it’s developed a way of doing this which involves looking up at the sky.

When humans navigate by the sun (during the daytime) or the stars (at night) they need to do some complex calculations, for a couple of reasons: (a) because they want to travel in a specific direction relative to the Earth’s surface, and (b) because journeys generally last several hours, during which time the positions of objects in the sky change. The beetle isn’t bothered by either of these considerations. It just sets off in a random direction, and wants to continue in that direction irrespective of the ups and downs of the terrain. And it only needs to travel a few metres, so objects in the sky aren’t going to move much.

The beetle doesn’t need a high resolution image of the sky – in fact quite the opposite. All it has to do is form a general impression of where the brightest part of the sky is, and then make sure this bright patch stays on the same relative bearing (“check sky – move forward – check sky – if bright patch has shifted counterclockwise turn slightly to the left – else if bright patch has shifted clockwise turn slightly to the right – repeat until destination is reached”).

But why does the beetle use the Milky Way? It’s a spiral galaxy consisting of a hundred billion stars, held together by gravity and dark matter. Isn’t that a rather sophisticated concept for an insect? Well no – the “concept” modern humans choose to attach to it is irrelevant. The Milky Way is just a distinctive feature in the night sky (in the clear skies of Egypt, where scarab beetles live). Having a low resolution imaging sensor, the beetle just looks for the brightest feature in its field of view. During the daytime, it uses the sun. At night, if there’s a moon, it uses the moon. If there isn’t a moon, it uses the Milky Way.

Actually the result isn’t as outrageous as it sounds. The problem is that people focus on the symbolic associations of words, rather than the underlying thing a word is being used to describe. So a really basic image-processing task, because of the way it’s described, suddenly takes on cosmic or mystical significance. The mystical dimension is enhanced by the fact that the dung beetle, under its alternative name of Scarab, was a sacred symbol in ancient Egypt that has now become a favourite of New Agers.

Stars also have a New Age connection, via astrology. This is one of the reasons – alongside associations with UFOs and science fiction – that any mention of “the stars” is likely to provoke a giggle reflex in the general public. But this is because people are focusing on the layers of associations superimposed on words, rather than what words actually mean. Living in the modern world, we have a complex mental model of what a star is. But from a purely empirical perspective, the stars are just points of light in the sky.

Needless to say, a scarab beetle doesn’t carry along any intellectual baggage regarding the scientific and cultural associations of the stars. It just knows it can see them, because they’re there (in this respect, the beetle is closer to reality than most humans, who read all about outer space on the internet but rarely look up at the night sky). From the beetle’s point of view, there is survival value in being able to travel in a straight line. By trial and error over countless generations, it’s developed a way of doing this which involves looking up at the sky.

When humans navigate by the sun (during the daytime) or the stars (at night) they need to do some complex calculations, for a couple of reasons: (a) because they want to travel in a specific direction relative to the Earth’s surface, and (b) because journeys generally last several hours, during which time the positions of objects in the sky change. The beetle isn’t bothered by either of these considerations. It just sets off in a random direction, and wants to continue in that direction irrespective of the ups and downs of the terrain. And it only needs to travel a few metres, so objects in the sky aren’t going to move much.

The beetle doesn’t need a high resolution image of the sky – in fact quite the opposite. All it has to do is form a general impression of where the brightest part of the sky is, and then make sure this bright patch stays on the same relative bearing (“check sky – move forward – check sky – if bright patch has shifted counterclockwise turn slightly to the left – else if bright patch has shifted clockwise turn slightly to the right – repeat until destination is reached”).

But why does the beetle use the Milky Way? It’s a spiral galaxy consisting of a hundred billion stars, held together by gravity and dark matter. Isn’t that a rather sophisticated concept for an insect? Well no – the “concept” modern humans choose to attach to it is irrelevant. The Milky Way is just a distinctive feature in the night sky (in the clear skies of Egypt, where scarab beetles live). Having a low resolution imaging sensor, the beetle just looks for the brightest feature in its field of view. During the daytime, it uses the sun. At night, if there’s a moon, it uses the moon. If there isn’t a moon, it uses the Milky Way.

Sunday, 15 September 2013

Reinventing Ezekiel's Wheel

Ezekiel was a priest who was exiled to Babylon along with King Jehoiachin of Judah in the sixth century BC. Ezekiel experienced a number of visions, and his account of these form one of the main prophetic books of the Hebrew scriptures. The best known of Ezekiel’s visions is the first, involving an encounter with a heavenly figure seated on a throne borne by four strange creatures, each of which has four faces and is supported by a “wheel within a wheel”.

This is one of the most striking images to be found in any of the Hebrew prophetic books, and as such has appealed to artists throughout the centuries. This depiction by William Blake (who had mystical visions of his own) emphasizes the mystical and symbolic nature of Ezekiel’s vision.

To many people, however, Ezekiel’s vision is nothing less than an extraterrestrial flying machine. As with other “ancient astronaut” theories, you often hear people says things like “Of course, that idea originated in 1968 with Erich von Däniken’s book Chariots of the Gods ”. Well, no it didn’t. All von Däniken did was to pitch the idea in populist, uncomplicated language that was capable of appealing to a huge mass-market audience. But the idea was by no means a new one.

”. Well, no it didn’t. All von Däniken did was to pitch the idea in populist, uncomplicated language that was capable of appealing to a huge mass-market audience. But the idea was by no means a new one.

I’ve already mentioned how ancient astronaut theories were pushed by Desmond Leslie as long ago as 1953, in one of the most famous of the early UFO books – Flying Saucers Have Landed, coauthored with George Adamski. Sadly the book is remembered solely for Adamski’s contribution, even though Leslie’s chapters are a lot more sophisticated and intelligent. British readers of my generation may also remember the work of W. Raymond Drake – the first of whose “Gods and Spacemen” books was published in 1964, four years before Chariots of the Gods. To my mind, Drake’s books were more insightful than von Däniken’s, and better researched. But writers like Drake and Leslie never achieved the mass appeal of von Däniken, and people forget (or were never aware) that they predated him by several years.

Although it’s frustrating that people give all the credit to the wrong person, if you look at it another way then von Däniken’s achievement is really quite impressive. He took an idea that had previously been confined to a small niche audience, and brought it to the attention of the whole world. In Fortean circles, however, everything he had to say was old hat. In his book Great World Mysteries, published in 1962, the British Fortean writer Eric Frank Russell wrote “...anything strange seen soaring above the clouds automatically became a fiery chariot. Some imaginative writers have seized on this fact and turned out stories depicting biblical characters as enlightened visitors from another world.”

To someone brought up in a technological, materialistic culture, it may seem obvious that ancient accounts of supposedly mystical experiences are garbled descriptions of extraterrestrial hardware. But the opposite is equally true – a modern-day account of extraterrestrial hardware may be a garbled description of a mystical experience. This is the line taken by the psychologist C.G. Jung in his 1959 book Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies. Jung uses Ezekiel’s vision as an example of what UFOs might be, not the other way around!

Perhaps the most mainstream reference to a “nuts and bolts” interpretation of Ezekiel’s vision is this short choral work composed by Ralph Vaughan Williams in 1956. By that time Vaughan Williams was 84 years old, and very much the grand old man of English classical music. The piece is a setting of the first chapter of the Book of Ezekiel, and the only unusual thing about it is the title the composer chose to give it: A Vision of Aeroplanes (the word “aeroplane” literally refers to an aircraft with a fixed horizontal lifting surface, but in the mid-20th century it was used loosely to mean any form of flying machine).

In an article about Vaughan Williams in issue 241 of Fortean Times (October 2008), David Sutton describes A Vision of Aeroplanes as “a cataclysmic sounding piece of musical prophecy – aeronauts from the future – for choir and organ”. But it’s odd that this particular composer should have chosen such a materialistic interpretation of the text, since the same FT article also describes Vaughan Williams as “a visionary in the tradition of Blake” (and for Blake’s distinctly non-materialistic interpretation, see above).

While most of the “nuts and bolts” proponents have been content to say “Ezekiel’s description sounds a bit like a flying machine”, some writers have gone further. In 1974, for example, an aeronautical engineer named J.F. Blumrich produced a full-length book called The Spaceships of Ezekiel. According to the author’s Foreword, this started out as an attempt to debunk the spaceship theory popularized by Eric von Däniken, but ended up supporting it – together with a fairly specific engineering design based on a line-by-line analysis of the Biblical text.

Although Blumrich’s book was the first detailed analysis to draw widespread attention, it wasn’t the first of its kind. Something very similar was attempted by Arthur W. Orton in 1961, in a 14-page article entitled “The Four-Faced Visitors of Ezekiel”. This appeared in Analog Science Fiction magazine, cover-dated March 1961 in the US and July 1961 in the UK. Again, Orton employed a line-by-line analysis of Ezekiel’s text to come up with a specific engineering design (although Orton’s design looks nothing like Blumrich’s).

The main point I wanted to make was that, contrary to popular opinion, Erich von Däniken wasn’t the first person to suggest a nuts-and-bolts interpretation of the Book of Ezekiel. Numerous lesser known authors put forward similar ideas throughout the 1950s and 60s – but on closer examination even they were merely “reinventing the wheel”. As long ago as 1902, a Baptist minister from Texas named Burrell Cannon was granted a patent for his Ezekiel Airship, which was supposedly based on the description provided in the first chapter of the Biblical account!

This is one of the most striking images to be found in any of the Hebrew prophetic books, and as such has appealed to artists throughout the centuries. This depiction by William Blake (who had mystical visions of his own) emphasizes the mystical and symbolic nature of Ezekiel’s vision.

To many people, however, Ezekiel’s vision is nothing less than an extraterrestrial flying machine. As with other “ancient astronaut” theories, you often hear people says things like “Of course, that idea originated in 1968 with Erich von Däniken’s book Chariots of the Gods

I’ve already mentioned how ancient astronaut theories were pushed by Desmond Leslie as long ago as 1953, in one of the most famous of the early UFO books – Flying Saucers Have Landed, coauthored with George Adamski. Sadly the book is remembered solely for Adamski’s contribution, even though Leslie’s chapters are a lot more sophisticated and intelligent. British readers of my generation may also remember the work of W. Raymond Drake – the first of whose “Gods and Spacemen” books was published in 1964, four years before Chariots of the Gods. To my mind, Drake’s books were more insightful than von Däniken’s, and better researched. But writers like Drake and Leslie never achieved the mass appeal of von Däniken, and people forget (or were never aware) that they predated him by several years.

Although it’s frustrating that people give all the credit to the wrong person, if you look at it another way then von Däniken’s achievement is really quite impressive. He took an idea that had previously been confined to a small niche audience, and brought it to the attention of the whole world. In Fortean circles, however, everything he had to say was old hat. In his book Great World Mysteries, published in 1962, the British Fortean writer Eric Frank Russell wrote “...anything strange seen soaring above the clouds automatically became a fiery chariot. Some imaginative writers have seized on this fact and turned out stories depicting biblical characters as enlightened visitors from another world.”

To someone brought up in a technological, materialistic culture, it may seem obvious that ancient accounts of supposedly mystical experiences are garbled descriptions of extraterrestrial hardware. But the opposite is equally true – a modern-day account of extraterrestrial hardware may be a garbled description of a mystical experience. This is the line taken by the psychologist C.G. Jung in his 1959 book Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies. Jung uses Ezekiel’s vision as an example of what UFOs might be, not the other way around!

Perhaps the most mainstream reference to a “nuts and bolts” interpretation of Ezekiel’s vision is this short choral work composed by Ralph Vaughan Williams in 1956. By that time Vaughan Williams was 84 years old, and very much the grand old man of English classical music. The piece is a setting of the first chapter of the Book of Ezekiel, and the only unusual thing about it is the title the composer chose to give it: A Vision of Aeroplanes (the word “aeroplane” literally refers to an aircraft with a fixed horizontal lifting surface, but in the mid-20th century it was used loosely to mean any form of flying machine).

In an article about Vaughan Williams in issue 241 of Fortean Times (October 2008), David Sutton describes A Vision of Aeroplanes as “a cataclysmic sounding piece of musical prophecy – aeronauts from the future – for choir and organ”. But it’s odd that this particular composer should have chosen such a materialistic interpretation of the text, since the same FT article also describes Vaughan Williams as “a visionary in the tradition of Blake” (and for Blake’s distinctly non-materialistic interpretation, see above).

While most of the “nuts and bolts” proponents have been content to say “Ezekiel’s description sounds a bit like a flying machine”, some writers have gone further. In 1974, for example, an aeronautical engineer named J.F. Blumrich produced a full-length book called The Spaceships of Ezekiel. According to the author’s Foreword, this started out as an attempt to debunk the spaceship theory popularized by Eric von Däniken, but ended up supporting it – together with a fairly specific engineering design based on a line-by-line analysis of the Biblical text.

Although Blumrich’s book was the first detailed analysis to draw widespread attention, it wasn’t the first of its kind. Something very similar was attempted by Arthur W. Orton in 1961, in a 14-page article entitled “The Four-Faced Visitors of Ezekiel”. This appeared in Analog Science Fiction magazine, cover-dated March 1961 in the US and July 1961 in the UK. Again, Orton employed a line-by-line analysis of Ezekiel’s text to come up with a specific engineering design (although Orton’s design looks nothing like Blumrich’s).

The main point I wanted to make was that, contrary to popular opinion, Erich von Däniken wasn’t the first person to suggest a nuts-and-bolts interpretation of the Book of Ezekiel. Numerous lesser known authors put forward similar ideas throughout the 1950s and 60s – but on closer examination even they were merely “reinventing the wheel”. As long ago as 1902, a Baptist minister from Texas named Burrell Cannon was granted a patent for his Ezekiel Airship, which was supposedly based on the description provided in the first chapter of the Biblical account!

Sunday, 14 July 2013

Dragon Symbolism

Here’s an unusual carved image that’s located just a few miles from where I live. Although I read about it some time ago, I only got round to stopping and having a look at it last week. It depicts a man battling a dragon, and it can be seen on the church of St Mary the Virgin at Stoke-sub-Hamdon. The oldest parts of the church were built during the Norman period around the year 1100, and that’s probably when this carving was produced.

Apart from the fact that a man fighting a dragon is an unusual thing to see on a church, there are a couple of striking things about the carving. The first is the clever way the arched back of the dragon fits neatly over the arch of the window (which is extremely narrow, even for the Norman period). The other is the cartoony style of the image, which is vaguely reminiscent of the Bayeux tapestry... which of course dates from around the same time.

The carving is on the exterior north wall of the church, which is a place where you often find pagan imagery on mediaeval churches (the north side was considered the “dark side” in those days). Although dragons were common in pagan folklore, this one may represent a Christianized legend. Having just done a bit of research, I’ve seen it confidently identified as “Saint Michael and the dragon” and as “Saint George and the dragon”. But Saint George is normally depicted on horseback, so personally I’d favour the first of these. There’s a hill about a mile from the church called St Michael’s Hill, which may or may not be significant.

Of course, after this lapse of time no-one can really know what legend the artist meant to depict. In a comment to my post last year about A Fortean History of Somerset, Richard Freeman mentioned that “the county also has more dragon legends than any other in the UK with a total of 11”. So who knows what the image would have meant to the 12th century inhabitants of Stoke-sub-Hamdon?

An almost universal characteristic among the dragons of European legend is that they’re bad. The majority are depicted as monsters that are just waiting to be slain by a hero (such as Saint George), while Saint Michael’s dragon was Satan himself, who was consigned to Hell. That’s a complete contrast to the dragons of Eastern tradition, which are seen as benevolent and auspicious. But there’s at least one benevolent and auspicious dragon on this side of the world, too – the Welsh dragon.

By coincidence, I saw a Welsh dragon here in England just a day after I took the photo at Stoke-sub-Hamdon. This was at a National Trust property called Bradley Manor, which is near Newton Abbot in Devon. The Great Hall there is decorated with a huge (and now partly obliterated) royal coat of arms dating from the Tudor period. This bears the familiar motto “Honi soit qui mal y pense”, but instead of the lion and unicorn it has a lion and... a dragon! (photography wasn’t permitted inside the house, so the picture here is a detail from the National Trust’s own image).

The unicorn is a symbol of Scotland, and was introduced by the Stuart monarchs who were also kings of Scotland. However, the Tudors who preceded them were a Welsh family, and so they used the dragon instead. The lion, of course, is a symbol of England. There may or may not be any significance to the fact that lions are real creatures whereas dragons and unicorns are the stuff of folklore!

Apart from the fact that a man fighting a dragon is an unusual thing to see on a church, there are a couple of striking things about the carving. The first is the clever way the arched back of the dragon fits neatly over the arch of the window (which is extremely narrow, even for the Norman period). The other is the cartoony style of the image, which is vaguely reminiscent of the Bayeux tapestry... which of course dates from around the same time.

The carving is on the exterior north wall of the church, which is a place where you often find pagan imagery on mediaeval churches (the north side was considered the “dark side” in those days). Although dragons were common in pagan folklore, this one may represent a Christianized legend. Having just done a bit of research, I’ve seen it confidently identified as “Saint Michael and the dragon” and as “Saint George and the dragon”. But Saint George is normally depicted on horseback, so personally I’d favour the first of these. There’s a hill about a mile from the church called St Michael’s Hill, which may or may not be significant.

Of course, after this lapse of time no-one can really know what legend the artist meant to depict. In a comment to my post last year about A Fortean History of Somerset, Richard Freeman mentioned that “the county also has more dragon legends than any other in the UK with a total of 11”. So who knows what the image would have meant to the 12th century inhabitants of Stoke-sub-Hamdon?

An almost universal characteristic among the dragons of European legend is that they’re bad. The majority are depicted as monsters that are just waiting to be slain by a hero (such as Saint George), while Saint Michael’s dragon was Satan himself, who was consigned to Hell. That’s a complete contrast to the dragons of Eastern tradition, which are seen as benevolent and auspicious. But there’s at least one benevolent and auspicious dragon on this side of the world, too – the Welsh dragon.

By coincidence, I saw a Welsh dragon here in England just a day after I took the photo at Stoke-sub-Hamdon. This was at a National Trust property called Bradley Manor, which is near Newton Abbot in Devon. The Great Hall there is decorated with a huge (and now partly obliterated) royal coat of arms dating from the Tudor period. This bears the familiar motto “Honi soit qui mal y pense”, but instead of the lion and unicorn it has a lion and... a dragon! (photography wasn’t permitted inside the house, so the picture here is a detail from the National Trust’s own image).

The unicorn is a symbol of Scotland, and was introduced by the Stuart monarchs who were also kings of Scotland. However, the Tudors who preceded them were a Welsh family, and so they used the dragon instead. The lion, of course, is a symbol of England. There may or may not be any significance to the fact that lions are real creatures whereas dragons and unicorns are the stuff of folklore!

Labels:

Architecture,

Art,

Cryptozoology,

folklore,

legends,

Saints,

Symbolism

Sunday, 7 April 2013

Phascinating Phacts

Of all the words in the English language, “fascinating” has one of the oddest derivations. In modern usage the word simply means “very interesting”, with vague overtones of “mesmerizing” or “casting a spell on”. But it originates from the old Latin word fascinus, which referred to a special kind of charm or amulet taking the form of an erect human phallus (sometimes with wings). Phallic charms of this type were extremely popular in the days of ancient Rome, when it was believed they had the power to ward off evil influences. If you type “fascinus” into a Google image search you’ll see the sort of thing I’m talking about.

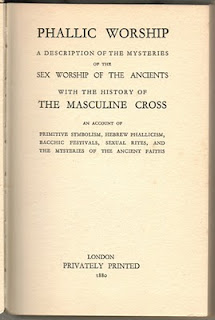

Phallic symbolism was surprisingly common in ancient religions, as I pointed out in my post on A Victorian Theology of Everything a couple of years ago. The book I referred to in that post was one I’d found in a second-hand bookshop, and at the time I had no idea who the anonymous author was. I’ve since discovered that it was a man named Hargrave Jennings (1817–1890), who seems to have more or less invented the subject of “phallicism”, and then devoted his whole career to writing about it.

Widespread as they are, phallic icons and amulets are usually purely symbolic in nature. But there’s one example—in fiction, at least—where it’s the real thing: the Talisman of Set. This features in one of the best occult novels of the twentieth century – Dennis Wheatley’s The Devil Rides Out, first published in 1934. The novel was used as the basis for a 1967 Hammer film of the same title, which (within the limitations of the 90 minute format) is reasonably faithful to the book. The screen version omits large chunks of occult background, but the basic plot is preserved, as well as a surprising amount of Wheatley’s dialogue. But the film doesn’t mention the Talisman of Set.

One of the main characters (in both the book and the film) is a young man named Simon, who is being pursued by a Crowleyesque occultist called Mocata. In the film, the reason why Mocata is so desperate to get hold of Simon is never explained – you just have to take it for granted. But the book goes into much more detail: Simon has discovered the secret of the Talisman of Set. This object, which is supposed to have been lost and found countless times throughout history, is nothing less than the mummified phallus of the Egyptian God Osiris! And unlike a Roman fascinus, this is no lucky charm – “whenever it is found it brings calamity upon the world” (it was given its sinister powers by Set, the brother of Osiris – hence its name). In 1914, the Talisman of Set had unleashed the Great War on the world, and now (in the 1930s) Mocata wants to use it to trigger a second global war.

Despite being the procreative organ of one of the most powerful gods in the Egyptian pantheon, the Talisman—when it’s finally tracked down—isn’t much to look at: “a small black cigar-shaped thing, which was slightly curved”. Eventually Mocata is defeated, and (in the novel) the Talisman of Set is duly incinerated... thus averting the threat of a Second World War. In reality, of course, the Second World War wasn’t averted... so perhaps that’s why Hammer decided to omit the Talisman of Set from the movie version. Or then again, maybe they were worried that the sight of Christopher Lee and Charles Gray chasing across Europe in pursuit of a shrivelled black phallus wouldn’t have gone down too well with the viewing public!

Phallic symbolism was surprisingly common in ancient religions, as I pointed out in my post on A Victorian Theology of Everything a couple of years ago. The book I referred to in that post was one I’d found in a second-hand bookshop, and at the time I had no idea who the anonymous author was. I’ve since discovered that it was a man named Hargrave Jennings (1817–1890), who seems to have more or less invented the subject of “phallicism”, and then devoted his whole career to writing about it.

Widespread as they are, phallic icons and amulets are usually purely symbolic in nature. But there’s one example—in fiction, at least—where it’s the real thing: the Talisman of Set. This features in one of the best occult novels of the twentieth century – Dennis Wheatley’s The Devil Rides Out, first published in 1934. The novel was used as the basis for a 1967 Hammer film of the same title, which (within the limitations of the 90 minute format) is reasonably faithful to the book. The screen version omits large chunks of occult background, but the basic plot is preserved, as well as a surprising amount of Wheatley’s dialogue. But the film doesn’t mention the Talisman of Set.

One of the main characters (in both the book and the film) is a young man named Simon, who is being pursued by a Crowleyesque occultist called Mocata. In the film, the reason why Mocata is so desperate to get hold of Simon is never explained – you just have to take it for granted. But the book goes into much more detail: Simon has discovered the secret of the Talisman of Set. This object, which is supposed to have been lost and found countless times throughout history, is nothing less than the mummified phallus of the Egyptian God Osiris! And unlike a Roman fascinus, this is no lucky charm – “whenever it is found it brings calamity upon the world” (it was given its sinister powers by Set, the brother of Osiris – hence its name). In 1914, the Talisman of Set had unleashed the Great War on the world, and now (in the 1930s) Mocata wants to use it to trigger a second global war.

Despite being the procreative organ of one of the most powerful gods in the Egyptian pantheon, the Talisman—when it’s finally tracked down—isn’t much to look at: “a small black cigar-shaped thing, which was slightly curved”. Eventually Mocata is defeated, and (in the novel) the Talisman of Set is duly incinerated... thus averting the threat of a Second World War. In reality, of course, the Second World War wasn’t averted... so perhaps that’s why Hammer decided to omit the Talisman of Set from the movie version. Or then again, maybe they were worried that the sight of Christopher Lee and Charles Gray chasing across Europe in pursuit of a shrivelled black phallus wouldn’t have gone down too well with the viewing public!

Saturday, 8 December 2012

Dante’s Divine Comic Book

Dante Alighieri (circa 1265 - 1321) is one of the most famous figures of European literature... and also one of the earliest. Although commonly associated with the Florentine Renaissance, he actually predated people like Botticelli and Michelangelo by two hundred years. The famous portrait of him in Florence Cathedral (left) wasn’t painted until more than a century after his death.

Dante’s most famous work is a long narrative poem called The Divine Comedy. This is in three parts, containing detailed descriptions of, in turn, Hell, Purgatory and Paradise. Not surprisingly, the first part—called the Inferno (which is simply the Italian word for Hell)—is the best-known and most popular. I bought my copy from a second-hand bookshop in Cambridge when I was a student in 1977, and—despite several abortive attempts—I still haven’t read it. It’s one of those books, like Finnegans Wake, that in spite of being one of the coolest things ever written just sits there on the bookshelf, decade after decade, not getting read.

What’s needed, of course, is a nice reader-friendly comic-book version of Dante's Inferno . And that’s exactly what Hunt Emerson has just produced (available from largecow.com). Hunt is best known to Forteans for his long-running Phenomenonix feature in Fortean Times, but he’s also produced what might be described as “intelligent but irreverent” comic-book adaptations of various literary works ranging from the Book of Leviticus (with Alan Moore) to the Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Coleridge. And now he’s done the same for Dante.

. And that’s exactly what Hunt Emerson has just produced (available from largecow.com). Hunt is best known to Forteans for his long-running Phenomenonix feature in Fortean Times, but he’s also produced what might be described as “intelligent but irreverent” comic-book adaptations of various literary works ranging from the Book of Leviticus (with Alan Moore) to the Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Coleridge. And now he’s done the same for Dante.

The complete poem of the Inferno is over 4700 lines long, so in a 71-page comic adaptation it’s inevitable that you end up with a somewhat condensed version of the original. For example, there is no mention in the comic book of Saladin in Limbo. On the other hand, when Dante meets the group of classic poets in Limbo he has to put up with a couple of pages of really bad limericks, which I’m sure aren’t in the original. People who are used to Hunt Emerson’s style will be expecting this sort of thing... although according to the helpful endnotes by Kevin Jackson, the adaptation is surprisingly faithful to Dante. [I thought I'd found an error in that the comic puts Aristotle in Limbo, who doesn't appear by name in Dante's version... but he is referred to obliquely as "the Master of those who know". Thanks to Kevin Jackson for putting me right on this!]

As well as giving the reader a vivid picture of the topography of Hell, as envisaged by Dante, Hunt Emerson’s version also provides an interesting insight into the nature of Dante’s poem itself. It really is a work of the Renaissance, and couldn’t be anything else. If it had been written earlier, during the darkest days of the Middle Ages, it would have been a simple warning to sinners about the dire punishments awaiting them in the afterlife, presented in a pious framework of the accepted Christian cosmology and demonology of the time (the same would have been true if it had been written centuries later, in a post-Reformation Protestant country).

In fact, the poem draws heavily on the pre-Christian mythology of Europe, and of Italy in particular, for its symbolism and terms of reference. But the thing that really comes across loud and clear is that Dante wasn’t as interested in providing a warning to future sinners as he was in cataloguing the misdeeds and torments of all the specific individuals who’d pissed him off over the years. To quote Dante (the comic-book version, that is) “... Hell was a sort of personal revenge theme-park, dedicated to getting back at all the bastards that have done me down in my life.” In other words, Dante’s Inferno isn’t pious moralizing, it’s satire. That’s why it’s great literature – and it took a comic-book to bring that point home to me!

Now, if only Hunt Emerson could be persuaded to take on Finnegans Wake...

Dante’s most famous work is a long narrative poem called The Divine Comedy. This is in three parts, containing detailed descriptions of, in turn, Hell, Purgatory and Paradise. Not surprisingly, the first part—called the Inferno (which is simply the Italian word for Hell)—is the best-known and most popular. I bought my copy from a second-hand bookshop in Cambridge when I was a student in 1977, and—despite several abortive attempts—I still haven’t read it. It’s one of those books, like Finnegans Wake, that in spite of being one of the coolest things ever written just sits there on the bookshelf, decade after decade, not getting read.

What’s needed, of course, is a nice reader-friendly comic-book version of Dante's Inferno

The complete poem of the Inferno is over 4700 lines long, so in a 71-page comic adaptation it’s inevitable that you end up with a somewhat condensed version of the original. For example, there is no mention in the comic book of Saladin in Limbo. On the other hand, when Dante meets the group of classic poets in Limbo he has to put up with a couple of pages of really bad limericks, which I’m sure aren’t in the original. People who are used to Hunt Emerson’s style will be expecting this sort of thing... although according to the helpful endnotes by Kevin Jackson, the adaptation is surprisingly faithful to Dante. [I thought I'd found an error in that the comic puts Aristotle in Limbo, who doesn't appear by name in Dante's version... but he is referred to obliquely as "the Master of those who know". Thanks to Kevin Jackson for putting me right on this!]

As well as giving the reader a vivid picture of the topography of Hell, as envisaged by Dante, Hunt Emerson’s version also provides an interesting insight into the nature of Dante’s poem itself. It really is a work of the Renaissance, and couldn’t be anything else. If it had been written earlier, during the darkest days of the Middle Ages, it would have been a simple warning to sinners about the dire punishments awaiting them in the afterlife, presented in a pious framework of the accepted Christian cosmology and demonology of the time (the same would have been true if it had been written centuries later, in a post-Reformation Protestant country).

In fact, the poem draws heavily on the pre-Christian mythology of Europe, and of Italy in particular, for its symbolism and terms of reference. But the thing that really comes across loud and clear is that Dante wasn’t as interested in providing a warning to future sinners as he was in cataloguing the misdeeds and torments of all the specific individuals who’d pissed him off over the years. To quote Dante (the comic-book version, that is) “... Hell was a sort of personal revenge theme-park, dedicated to getting back at all the bastards that have done me down in my life.” In other words, Dante’s Inferno isn’t pious moralizing, it’s satire. That’s why it’s great literature – and it took a comic-book to bring that point home to me!

Now, if only Hunt Emerson could be persuaded to take on Finnegans Wake...

Saturday, 18 August 2012

The portrait with a life of its own

The image above, which was taken by Paul Jackson in 2001, shows the mural sculpture of Che Guevara in the Plaza de la Revolución in the Cuban capital of Havana. It is based on a black-and-white picture taken by newspaper photographer Alberto Korda: just one of many snaps he took at a rally in Havana in 1960. Amongst many other public figures, this was the only useable picture of Che, but Korda realized it was something special -- and worthy of more than an ephemeral place in a newspaper report. He called the picture Guerrillero Heroico, and it is the most reproduced image in the history of photography.

In 2006, I went to an exhibition in London entitled Che Guevara: Revolutionary and Icon. Because Che is such an important historical figure, you might guess the exhibition took place at the British Museum, but it didn’t. Because Korda’s photograph is one of the most instantly recognizable portraits in history, you might think the exhibition was at the National Portrait Gallery, but it wasn’t there either. It was at the Victoria and Albert Museum, which is London’s premier museum for the decorative arts and design. Besides being one of history’s most famous Marxist revolutionaries and freedom fighters, Che Guevara has – in opposition to everything people normally associate with Marxist revolutionaries and freedom fighters – become one of the world’s greatest style icons.

According to the V&A publicity material, “Korda’s famous photograph first deified Che and then turned him into an icon of radical chic. Its story – a complex mesh of conflicting narratives – has given Heroic Guerrilla a life of its own, an enduring fascination independent from Che himself.” For every appropriate place that the image is seen – such as the Plaza de la Revolución in Havana – it can be found in a thousand inappropriate places, such as on T-shirts, bags and mugs that have more to do with mass market consumerism and US-style celebrity culture than with Marxist idealism or Latin American independence. As the V&A says, “to wear Che’s image today can be a declaration of radical defiance or a vague statement of cool, depending on the place and context.”

A paradoxical thing about having one of the most instantly recognisable faces in the world is that, if you want to adopt an impenetrable disguise, all you have to do is shave and get a haircut! That’s exactly what Che did when he adopted the fake identity of Adolfo Mena González during his ill-fated mission to Bolivia in 1966. The picture below may not look much like Che Guevara, but it can’t hide the fact that he was an extraordinarily photogenic individual!

In 2006, I went to an exhibition in London entitled Che Guevara: Revolutionary and Icon. Because Che is such an important historical figure, you might guess the exhibition took place at the British Museum, but it didn’t. Because Korda’s photograph is one of the most instantly recognizable portraits in history, you might think the exhibition was at the National Portrait Gallery, but it wasn’t there either. It was at the Victoria and Albert Museum, which is London’s premier museum for the decorative arts and design. Besides being one of history’s most famous Marxist revolutionaries and freedom fighters, Che Guevara has – in opposition to everything people normally associate with Marxist revolutionaries and freedom fighters – become one of the world’s greatest style icons.

According to the V&A publicity material, “Korda’s famous photograph first deified Che and then turned him into an icon of radical chic. Its story – a complex mesh of conflicting narratives – has given Heroic Guerrilla a life of its own, an enduring fascination independent from Che himself.” For every appropriate place that the image is seen – such as the Plaza de la Revolución in Havana – it can be found in a thousand inappropriate places, such as on T-shirts, bags and mugs that have more to do with mass market consumerism and US-style celebrity culture than with Marxist idealism or Latin American independence. As the V&A says, “to wear Che’s image today can be a declaration of radical defiance or a vague statement of cool, depending on the place and context.”

A paradoxical thing about having one of the most instantly recognisable faces in the world is that, if you want to adopt an impenetrable disguise, all you have to do is shave and get a haircut! That’s exactly what Che did when he adopted the fake identity of Adolfo Mena González during his ill-fated mission to Bolivia in 1966. The picture below may not look much like Che Guevara, but it can’t hide the fact that he was an extraordinarily photogenic individual!

Sunday, 3 June 2012

Crashed UFO in London

Hot on the heels of his Alien skull simulacrum, Paul Jackson has obtained further photographic evidence of extraterrestrial visitation in the form of this crashed flying saucer, which he spotted near his hotel while staying in London last week. I assume it’s meant to be some form of abstract sculpture, although Paul said he couldn’t see an identifying plaque on it, and his own caption confidently reads “A crashed UFO in Canada Square, Canary Wharf”.

Looking through Paul’s album from his London trip, another vaguely Fortean picture is this statue by Enzo Plazotta called Homage to Leonardo, which stands in Belgrave Square. It’s modelled after Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man” drawing, which features prominently in the early chapters of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. But the image is interesting in its own right as a depiction of the Hermetic symbolism of the individual as a “microcosm within the macrocosm”.

Looking through Paul’s album from his London trip, another vaguely Fortean picture is this statue by Enzo Plazotta called Homage to Leonardo, which stands in Belgrave Square. It’s modelled after Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man” drawing, which features prominently in the early chapters of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. But the image is interesting in its own right as a depiction of the Hermetic symbolism of the individual as a “microcosm within the macrocosm”.

Sunday, 20 May 2012

Bacchus and Ariadne

Here is a picture for anyone who thinks classical mythology and/or renaissance art is dull. It’s the work of the 16th century Italian artist Agostino Carracci, and it depicts the legendary tale of Bacchus and Ariadne. In Greek mythology, Ariadne was a Cretan princess who fell in love with the hero Theseus. He dumped her on the island of Naxos, where shortly afterwards the god Bacchus arrived to help her get over him. While the legendary account has them indulging in a robust sex session, it’s not often depicted as explicitly as it is here! A more traditional version was produced by Agostino’s brother Annibale Carracci.

It was not unknown for artists to produce generic porn images and slap classical-sounding titles on them to “get them past the censor”. But that’s not the case here, since the scene really does depict the legend of Bacchus and Ariadne. The male figure is wearing a wreath of vine-leaves, which was a universally recognized symbol of the god Bacchus. And in the background you can see Theseus making a getaway in his ship... again a widely recognized symbol often seen in depictions of this story.

Bacchus is often euphemistically described as the “god of wine”, but actually he was the god of drunkenness, debauchery and all-night sex orgies. Not surprisingly he had a large cult following, particularly in the decadent times of the later Roman Empire. We even used to worship him here in Somerset, as can be seen from this (sadly rather damaged) statue in the Roman ruins at Bath.

It was not unknown for artists to produce generic porn images and slap classical-sounding titles on them to “get them past the censor”. But that’s not the case here, since the scene really does depict the legend of Bacchus and Ariadne. The male figure is wearing a wreath of vine-leaves, which was a universally recognized symbol of the god Bacchus. And in the background you can see Theseus making a getaway in his ship... again a widely recognized symbol often seen in depictions of this story.

Bacchus is often euphemistically described as the “god of wine”, but actually he was the god of drunkenness, debauchery and all-night sex orgies. Not surprisingly he had a large cult following, particularly in the decadent times of the later Roman Empire. We even used to worship him here in Somerset, as can be seen from this (sadly rather damaged) statue in the Roman ruins at Bath.

Labels:

Archaeology,

Art,

legends,

mythology,

Sacred sex,

Symbolism

Sunday, 6 May 2012

Ambiguous Symbolism

Here is another photograph from my recent visit to London. This was taken in the Victoria and Albert Museum, and shows a wooden model of Jesus riding on a donkey. It was made in Southern Germany around 1480, and according to the caption “On Palm Sunday it was drawn through the streets to commemorate his triumphal entry into Jerusalem”. If I’d seen it a month ago, it might have been topical!

There is something jarringly contradictory about the juxtaposition of a donkey and the phrase “triumphal entry”. To human eyes, a donkey is a comically awkward-looking creature. Compared with a horse, camel or elephant, the sight of a grown man riding on one is anything but dignified. This isn’t just a modern perception -- even the Old Testament prophet Zechariah talks about the future Messiah “humble and riding on a donkey”.

But humble is a relative term. What if there are strict rules against riding on any kind of animal? In that case, riding on a donkey is transformed from a symbol of humility to a symbol of power (made even more powerful in light of Zechariah’s prophecy). According to Lynn Picknett and Clive Prince in The Masks of Christ , “At Passover, it was the custom to enter Jerusalem on foot as a sign of humility. The people should have been offended that he was riding into the holy city on the back of an animal. If they were happy with the arrangement, they must have recognized him as a special person to whom the usual customs no longer applied.”

, “At Passover, it was the custom to enter Jerusalem on foot as a sign of humility. The people should have been offended that he was riding into the holy city on the back of an animal. If they were happy with the arrangement, they must have recognized him as a special person to whom the usual customs no longer applied.”

There is something jarringly contradictory about the juxtaposition of a donkey and the phrase “triumphal entry”. To human eyes, a donkey is a comically awkward-looking creature. Compared with a horse, camel or elephant, the sight of a grown man riding on one is anything but dignified. This isn’t just a modern perception -- even the Old Testament prophet Zechariah talks about the future Messiah “humble and riding on a donkey”.

But humble is a relative term. What if there are strict rules against riding on any kind of animal? In that case, riding on a donkey is transformed from a symbol of humility to a symbol of power (made even more powerful in light of Zechariah’s prophecy). According to Lynn Picknett and Clive Prince in The Masks of Christ

Sunday, 29 April 2012

Enigmatic Art

A few months ago I wrote an item about the awesome apocalyptic paintings of John Martin (1789 -1854) that were on show at the time at the Tate Britain museum in London. I went there again last week, and I have to say the museum’s permanent collection is pretty dull in comparison with the Martin exhibit. At first glance the picture above looks like it might be one of Martin’s works, and it does depict the Biblical tale of The Destruction of Sodom which is exactly the sort of subject Martin specialized in. On closer inspection, however, it simply isn’t vivid enough -- the architecture and human figures are too vaguely drawn and hazy. Actually the picture is by Martin’s much more famous contemporary J.M.W. Turner (1775 -1851). If you think the picture looks too good to be a Turner, that’s because I “improved” it by enhancing the colours and contrast. The original, shown below, looks exactly like any other painting by Turner!

Another unusual picture I saw in the Tate is shown below. This dates from the late Elizabethan period -- to put it in context, that’s around the time Shakespeare’s plays were written. It depicts an “average man” praying to heaven as he is beset by woes from all sides. The picture is highly symbolic, with most of the figures dressed in a classically timeless style... except the woman on the left, who is wearing what must have been the high fashion of the time. For some reason this struck me as a distinctly kinky touch, especially as one of her three arrows is labelled “lechery”!

Since my own photograph didn’t come out very well, what is shown here is a detail from the Tate’s own image. You can see the full version here, together with a transcription of the various labels.

Another unusual picture I saw in the Tate is shown below. This dates from the late Elizabethan period -- to put it in context, that’s around the time Shakespeare’s plays were written. It depicts an “average man” praying to heaven as he is beset by woes from all sides. The picture is highly symbolic, with most of the figures dressed in a classically timeless style... except the woman on the left, who is wearing what must have been the high fashion of the time. For some reason this struck me as a distinctly kinky touch, especially as one of her three arrows is labelled “lechery”!

Since my own photograph didn’t come out very well, what is shown here is a detail from the Tate’s own image. You can see the full version here, together with a transcription of the various labels.

Saturday, 24 December 2011

The Mystic Nativity

Botticelli's Mystic Nativity is one of the best known paintings in the National Gallery in London. One of the reasons it's called "Mystic" is because the painting is full of symbolism taken from the Book of Revelation. This is stated explicitly in a Greek inscription at the top of the picture, together with the date it was painted: the year 1500. Now 1500 may not be quite as round a number as 1000 or 2000, but it was round enough to attract its share of "End of the World" prophecies -- including the Second Coming of Christ, which is what Botticelli was alluding to in this painting.

As well as its religious symbolism, The Mystic Nativity is important for its "mystical" artistic style, which had a major influence on British painting of the Victorian period -- in particular that of the Pre-Raphaelites (in the year 1500 Raphael was 17 years old whereas Botticelli was 55 -- so he was literally a pre-Raphaelite!).

At this point it would be logical to include an image of The Mystic Nativity, but it's such a hackneyed Christmas image that I won't bother (there's a good zoomable version on the National Gallery website). Instead, here is a less well-known Nativity painting in the Pre-Raphaelite style. This is a huge watercolour by Sir Edward Burne-Jones called The Star of Bethlehem, which was painted in 1890 for the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. To me this captures the essence of the word "mysticism" much better than the Botticelli version.

As well as its religious symbolism, The Mystic Nativity is important for its "mystical" artistic style, which had a major influence on British painting of the Victorian period -- in particular that of the Pre-Raphaelites (in the year 1500 Raphael was 17 years old whereas Botticelli was 55 -- so he was literally a pre-Raphaelite!).

At this point it would be logical to include an image of The Mystic Nativity, but it's such a hackneyed Christmas image that I won't bother (there's a good zoomable version on the National Gallery website). Instead, here is a less well-known Nativity painting in the Pre-Raphaelite style. This is a huge watercolour by Sir Edward Burne-Jones called The Star of Bethlehem, which was painted in 1890 for the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. To me this captures the essence of the word "mysticism" much better than the Botticelli version.

Wednesday, 2 November 2011

Descent into Limbo

Here is an unusual painting I saw in the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery a couple of days ago. If you look carefully (click on the image and then click "Show original" to see a larger version) there are a number of odd things about the picture, but perhaps the most obvious is that it depicts Christ in a rather unflattering rear view. They say you should never turn your back on the audience, but that is exactly what Jesus is doing here! His identity is indicated by a halo and by the "Banner of the Resurrection" -- symbolism that would have been instantly recognizable in 1475 when the picture was painted.

The painting is entitled The Descent of Christ into Limbo, and is the work of the Venetian artist Giovanni Bellini. It is loosely based on an engraving by Bellini's brother-in-law, Andrea Mantegna. The scene depicted was very popular in medieval Christianity, even though it is not mentioned at all in the Bible. The idea is that, during the three days between Christ's death and the Resurrection, he descended into Hell to rescue all the Old Testament Patriarchs and Prophets who had been incarcerated there. The first to be released were Adam and Eve, together with their "good" son Abel: these are the three naked figures on the right of the picture (Abel's brother Cain, as the world's first murderer, was left in Hell).

The story of Christ's decent into Hell was first told in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, written several centuries after the canonical gospels. In the original version, the idea was that the Patriarchs and Prophets were suffering in Hell along with regular sinners, but as time went on theologians decided they weren't happy with this. They invented the concept of "Limbo" (a Latin word meaning "edge") which was a relatively nice part of Hell reserved for virtuous but unbaptized individuals.

By the time of the renaissance, when educated Christians were developing a new respect for the pre-Christian culture of ancient Greece and Rome, the idea of Limbo became indispensable. When Dante wrote his Divine Comedy in the early 14th century, it was in Limbo that he met his tour guide, the Roman poet Virgil. The latter still had a clear recollection of Christ's visit: "I beheld the arrival of a Mighty One, crowned with the token of victory. He delivered from this place the shade of our first parent and of Abel his son, and that of Noah, and of Moses the lawgiver and servant of God; Abraham the patriarch and David the king, Israel with his father and his sons and Rachel for whom he served so long, and many more; and he made them blessed."